It’s frightening how little the West understands The People’s Republic of China. And what we don’t know is hurting us — and them. Inside China’s borders resides the largest population on the planet (1.357 billion compared to the United States’ paltry 318 million), which is guarded by the largest army in terms of active personnel and a formidable nuclear arsenal. China also hosts one of the fastest growing economies, and as a result, the planet’s largest middle class. The Republic is therefore revered by more open capitalist cultures as much as it is feared.

Those within China who have benefited from its unprecedented prosperity have paid a high price, however, in terms of freedom of expression and oppression. Meanwhile the foreign corporations that do business there, in order to continue to reap the rewards of China’s burgeoning markets, choose to turn a blind eye to these human rights abuses — they have to, since it’s the only way the state allows them to function. Thus, the Chinese government and the overseas corporations doing business within the Republic’s borders are essentially in cahoots in maintaining the status quo; The Great Wall of China is no longer a physical one protecting the insular nation, but one built on silence.

Enter documentarian Vanessa Hope, whose previous credits include William Kunstler: Disturbing the Universe and China in Three Words. Through the language of film, Vanessa — who has dedicated her personal and professional life to exploring China’s culture — hopes to foster greater understanding and break the state imposed and business endorsed wall of silence.

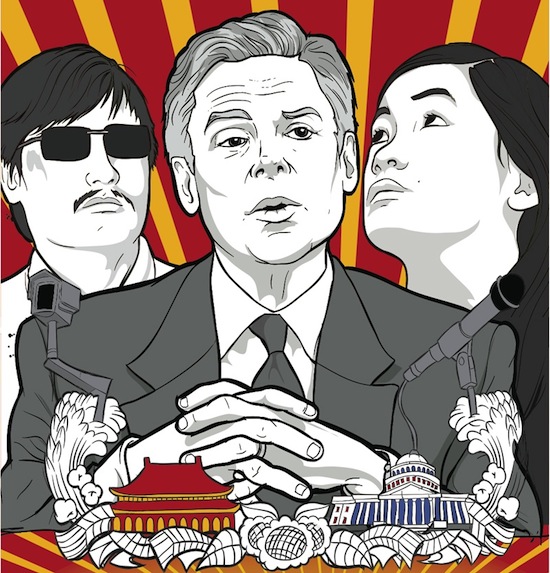

Her latest project All Eyes And Ears is remarkable, both in terms of scope and access. Through Vanessa’s lens, we follow the former Mormon Governor of Utah, Jon Huntsman, as he moves to China with his glamorous wife Mary Kaye and their adopted Chinese daughter Gracie to take up office as the Obama-appointed U.S. Ambassador. Vanessa took a longitudinal approach, filming over the course of five years from the end of 2009 through the beginning of 2014. Consequently, Huntsman’s term in office and Vanessa’s film bears witness not ony to the rise of authoritarian leader Xi Jinping, but also the rise of the proletariat in the Occupy-inspired Jasmine Spring. The arc of Huntsman’s story also converges with that of the blind, self-taught Chinese human rights lawyer Chen Guangcheng, who escaped from house arrest in 2012 to claim asylum at the U.S. Embassy in Beijing. This unexpected turn of events, which occurred during a key international diplomatic summit, sparked one of the greatest crisis in U.S. / China relations in recent times.

We caught up with Vanessa by phone to talk about the project. The following Q&A has been edited for clarity and length.

Nicole Powers: What inspired you to do a film about China?

Vanessa Hope: I got into China when I took an East Asian history class my last year of high school. I fell in love with a book called The Woman Warrior by Maxine Hong Kingston. I was really curious about the language... Once you start that process it's hard to stop, because it's so challenging that you need to really commit to at least a few years before you can even really speak in Chinese. I started traveling there to work on the language and to teach. The people you meet in China who are also committed to studying Chinese and learning about China are pretty great. I've kept a lot of those friends over the years, and I just got hooked.

NP: It's not easy for Westerners to get access to film in China and you had unprecedented access — not only within China and its far-flung provinces, but also with regards to the American Ambassador and his family. How did this all come about? Did the idea for the film or the opportunity come about first?

VH: The idea came about first. I really wanted to share the stories of an American lawyer who was one of the first to go to China and help them build their legal system. His name is Jerome Alan Cohen, and he's one of those incredible storytellers. He's had these life experiences that are astounding and involve assassination attempts on the President of South Korea and teaching the President of Taiwan at Harvard Law School — things that people might find surprising. He loves to tell those stories, and he inspired me to want to make the movie with him to give an insight into the personal relationships people have when they study Chinese and start working in China.

But it was hard to get something financed with him. He brought me into the Ambassador's residence in Beijing under President Bush and I heard him essentially lobby the Ambassador about a human rights case, a Chinese lawyer was being persecuted. He wanted it brought to the Ambassador's attention, and he wanted something done about it. I thought that was fascinating and maybe if I could get access into whoever Obama would appoint to be an Ambassador, because I was excited about Obama becoming President, that would be a way into this story that people don't really know about. That was where it began.

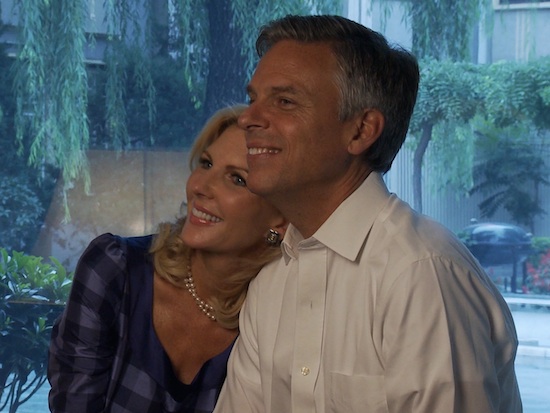

Photo: Former United States Ambassador to China Jon Huntsman and his wife, Mary Kaye.

Then I was really surprised when President Obama appointed a Republican Mormon Governor of Utah... I had met some people in the State Department who were trying to help me through the State Department channels find access to whoever Obama was going to appoint. That was slow. But there's a woman producer named Geralyn Dreyfous I had met through my husband... Geralyn basically said Huntsman is my Governor, you can stop waiting for official access to him through State Department channels, just come out here to Utah with a camera and a cinematographer, meet him, we'll pitch him the story, and we'll see what he says. So I did that.

There is a cinematographer I had just worked with on a movie in New York I had produced and she had shot. Her name is Magela Crosignani and she's from Uruguay but she was living in LA. We embarked on this adventure together. We land in Salt Lake City, Geralyn takes us to the Governor's Mansion, we sit down with the Huntsman's, Jon and Mary Kaye, and tell them it won't be a biopic about them, it will be them as a way into this larger story of what is going on between the two countries. They said okay, great, turn your cameras on. It just pretty much started the first day we were out there, and we just kept going along with it.

NP: It's an incredible story, because the arc of the Huntsman's story and Chen Guangcheng's are similar. The timing is perfect; by the end of the film their stories converge. From a structural point of view, events couldn't have turned out better for you as a filmmaker.

VH: Really, they couldn't have turned out better. Because the only way to tell a story with heavy issues for audiences to enjoy and find somewhat entertaining, or at least relatable or emotional, is through character. I was waiting with the Huntsman's in a kind of longitudinal view of their time in China as Ambassador. Then, when he ran for President, we felt like that was important too… We didn't really know what was going to happen. We were watching all the time and waiting to see. Then the Chen Guangcheng story and a few other stories unfolded pretty much simultaneously with his time running for President. We couldn't ignore it. It was so emblematic of that question of how we prioritize people, which Chen represents, fighting for them, for a rule of law to protect them, for civil society to help them, versus our business and security interests. The fact that this amazing legal advocate, human rights advocate lands in our embassy in the middle of a security and economic dialog pretty much emblemizes the whole story...

Photo: Chinese lawyer and human rights activist Chen Guangcheng.

NP: You don't really editorialize much in the film, you just allow us to follow as events unfold, and they very much speak for themselves. How much were you conscious of doing that? Because I know that you’ve very much dedicated your life to exploring the Chinese culture in your work and I would imagine that you were cognizant of having to be somewhat gentle from an editorial point of view in order to be allowed access back in the country for your next project.

VH: Yes, that's another great point. I have learned a lot in the making of the film about how insidious the propaganda machines of both countries are. I mean, when anyone wants to learn the language of another country and go spend time in another country, they're generally speaking keeping an open mind... They want to be empathetic, they want to understand the world from people in the foreign country's point of view, and take it all in, and get a new perspective on their own country. That's one of the great experiences of travel. I certainly went to China in an innocent enough way… I was a student at the time. When I went I was 18... It was a sensitive time in the early ‘90s after Tiananmen Square and I wasn't looking to create trouble, if that makes any sense. I was looking to understand what was going on, how people felt, and I was sensitive to their fears, their silence.

I'm really looking forward to Joshua Oppenheimer's The Look of Silence. He did The Act of Killing documentary. The Act of Killing was about the perpetrators of a genocide in Indonesia, but The Look of Silence is about the victims being silent, and you realize how cowed into silence people are in China on an everyday basis. They have to tell themselves that politics doesn't enter their daily lives, even though politics is all over their daily life...

What's difficult is that foreigners with business interests in China tend to contribute to the fear and silence of Chinese people. Most businesses want people to remain silent about what's really going on with the Chinese government and how it's treating its people, because that's the only way to do business with the Chinese government, because they'll censor you otherwise, or they'll put a black star by your name, or they'll keep you out of the country. At this moment in time, because the government in China has so much power, especially economically… there’s a big cone of silence around what's really going on. And I think it's not doing any service to people living in China who would benefit from greater transparency and openness. I'm not saying they need to be a democracy, but they certainly don't deserve to be living in an authoritarian county that Western countries are propping up out of fear and greed basically.

NP: Right. You follow the plight of Google in your movie. I guess that's actually one company that's maybe the exception; they decided the price that they would have to pay in terms of transparency and freedom of speech [and the damage it would do to their reputation internationally] didn’t make it worth continuing to do business with the country.

VH: Yes, thank you for pointing that out. That's a great example. They had learned from Yahoo, who had gone in and acquiesced to what the Chinese government demanded when they said without explaining the context to Yahoo, we need you to turn over all your data, your emails and personal information of people using your service — and then they used that to catch someone they felt was a human rights advocate stirring up trouble for them and Yahoo was a part of that. I think Google was aware of that kind of strategy and tactic on the part of the Chinese government, and, yeah, they didn't want to be used.

NP: You say it would be very easy to write a movie and create trouble, but what this film actually does is attempt to create understanding, which I feel is far more constructive. One of the biggest sticking points with relations with the West right now is the situation in Tibet, and one of the most fascinating nuggets of new information I got from the film was how the United States was partly responsible for that situation. The CIA deliberately destabilized the Tibetan region [in an effort to distract focus and resources from the Korean War] and actually escorted the Dalai Lama out of Tibet and into Dharamshala in India. We're here on our high horse saying that China needs to sort the Tibet situation out, but we helped create that situation in the first place.

VH: Yes, I found that story really fascinating too… A filmmaker, Robert Carl Cohen, did a documentary that was just a straight-up hour interview with a U.S. Ambassador named James Lilley about his time in China. In that interview, I learned that we had been going in to destabilize Tibet, so I asked questions about that… I think that part of creating understanding is going all the way to admit where we've made mistakes and apologize and try to acknowledge the past and then move forward. But… it's a propaganda tactic that the Chinese government uses, to use the past to impact the future and to play the victim when they need to play the victim to drum up nationalism and get Chinese people pissed off at the West for past mistakes or past problems.

NP: But then you also can't blame for being suspicious of our motives when America goes in and destabilizes a country in such a nefarious way. I mean, in the scheme of things, it's not that long ago.

VH: Fair enough. Okay, that's true on Tibet… But with Japan, I feel like that is World War II… I guess World War II is still a fresh wound for many, many people… But there is a level where playing the victim is a useful card for the government to drum up nationalism.

NP: Well America did it with 9/11 and we can continue to do it. Think of all of the human rights abuses that we've been guilty of in the name of 9/11. How long are we going to play that card?

VH: Yes, you're right. I wanted to make sure that I wasn't making America look innocent or perfect, or like we've always done the right thing, but to acknowledge that we haven't. To acknowledge what we've done wrong…

NP: I think that if we want the Chinese to fix Tibet, we actually need to apologize for our part in it.

VH: Yeah, you're right, absolutely... I mean one of the interesting things you also picked up on is how I'm not trying to make policy prescriptions with this movie. I'm not saying this is what America and China precisely need to do. I'm just trying to give you a feeling for what's going on and where both sides stand on many different issues and the mosaic and complexity of it. But the question of policy is real and people hopefully will look at it and say what you just said about Tibet, which is a great idea. You don't know whether that will work for the Chinese government, but it's worth a shot...

It's kind of a tipping point moment. Because it's more common for people to be speaking openly about how disappointed they are that the thought of bringing economic liberalization to China, would lead to some opening up politically but that idea is really dead right now. Xi Jinping is more authoritarian and repressive than many Chinese Presidents we've seen before… He's not interested in compromising, he is being more aggressive with territory... The last thing I would hope for is war, and I don't think that's likely to happen, except if there's an accident in the East or South China Sea. But it is a moment in time where people are reflecting on where we've come in the relationship, and what's going to happen in the future, and how to recalibrate how we're dealing with China.

NP: You've got some incredible footage with Jon Huntsman, especially at the end. He's incredibly candid with you. One of the most powerful things to me that he said was when he talks about how we've lost our credibility as a nation because of our wars — it’s especially powerful since it’s coming from a Republican,

VH: I know.

NP: That was very profound.

VH: Thank you for pointing that scene out too. That was really important to me. That was one of the last interviews. You know two of the most open interviews I got with Huntsman I think were after he quit the presidential race, and he was in a very reflective moment, possibly a slightly dark moment. I'm not a Republican, but I was pushing him, and he was open to these kinds of questions, and I appreciated that. Because for a long period of time people were saying, he's too much of a politician, you're not getting in there enough, you've got to break him... I'm not Barbara Walters or someone who can get you on TV and make you cry. I won't. I felt like I had to be able to sustain the relationship over time and build trust and understanding so I could let the story evolve to an interesting place. I didn't want to blow it by pissing him off and losing access early, so I tried to be relatively diplomatic. But I think once he quit the presidential race, he became more open, trust had been established, and that's when that interview happened.

Photo: Gracie Huntsman.

NP: One of the stars of this movie is undoubtedly his daughter Gracie, who almost became almost the de facto ambassador because she was so much a symbol of East-meets-West.

VH: Yeah.

NP: I love the way you handled her voiceovers. Obviously, she's not a trained voiceover artist, so rather than try to make it look slick and professional, you showed us the girl that she was, giggling when she got something wrong and playing with her phone… It made her much more human.

VH: Oh good, thank you. She was a very tricky character to get into the film. Because we discovered her importance in the edit watching the footage and seeing how much she meant to the Huntsmans and seeing how she was struggling to navigate her way between the two countries, where her loyalties lay. She was constantly being questioned about it and put on stage. I think the family generally feels accustomed to being in the spotlight, so that's not as big of an issue for them, and Gracie is just very composed and good in that sense in the spotlight. But to get her to be more open, we really had to focus on her and putting her in a recording room alone was something she really enjoyed.

It's funny because what we used was mostly her own answers to questions. But I had written these scripts that were pretty political, and she went along with it. I was trying to get a voice out there that was aware of what was going on between the two countries, and we realized that Gracie herself was more innocent and we should keep with who she is and let her shine as she is. So that ended up being the focus with her. There are a few lines that I had written that got in the movie, but even the ones that were written, had been inspired by her or something she had said, because I got to know her over time.

NP: You were trying to get her authentic voice?

VH: Yeah. I mean people chafe at a girl — let alone someone Gracie's age — being a key character in a story with these kinds of stakes and politics, and it was a risky choice... I feel like I wanted to empower her, and I have always felt slightly like an outsider in a man's world in exploring these issues. There's a very good YouTube parody ["Women Know Your Limits"], it's a British satire of women trying to speak up at a dinner party about currency issues and economics. The men shut them up and tell them they should be talking about kittens and sweeter subjects… It's very funny. I always had that in my head as I was like, hmm, I'm going to let Gracie be a big part of this because she can inspire other women, and I think it would be a good thing.

NP: I’m going to be interested to see what she does as an adult.

VH: Yes, yes.

NP: A lot of the stuff that we see in the media about China is very much stereotypical footage of peasants or visions of Tiananmen Square, where there's a very visceral sense of oppression. What you show, and what you talk about too — and I think is the flip side of the coin and is one of the reasons that the Chinese government can get away with what they're able to get away with domestically — is that to some extent, they're delivering. You talk about the prosperity of the middle class, and more importantly you show the prosperity of the middle class. For all of China's flaws, it's not failing the middle class in the way that American is.

VH: I'm so glad you're pointing this out. This is particularly funny because I was just in Cannes and… basically long story short, there's this hot-shot French sales agent, who hasn’t seen our film, he's just giving random advice. He knows it's a film about China, and he's letting me know that the market is down in Europe, and it's tough times. And because I'm an American with an American indie film it's going to be up against European films that get subsidies… and I can't get that etcetera. But he also said, by the way China's a bad topic; No one really wants to be thinking about them because they have all the money and the only thing that makes us feel good is when we see them suffer, suffer, suffer, so we confirm that our lifestyle is better… There's a real grain of truth in what he was saying, sadly, despite his joking tone. Like the documentary films that do get out there about China, they do tend to be just the suffering…

NP: Well in the West, we want to feel superior to China, especially since we're mortgaged up to the hilt to them.

VH: I'm trying to give the positive and the negative. I think you're either getting stories about China that are just people suffering and more of a stereotypical image of farmers and peasants maybe migrating to the city. Or you're getting the glitzy, glammy everything's rich and fantastic here story, that's not looking at anything difficult that's really going on in people's lives. So, yeah, I wanted to make sure I got both in.

NP: You very much got as much China in there as you possibly could — both in terms of class and also in terms of geography. Because taking a 25-hour train journey to Tibet, and nearly getting thrown off in the middle of nowhere, that’s quite an undertaking.

VH: Yes, very true.

NP: That must have been quite an adventure.

VH: Yeah, it was.

NP: What was the process of even getting permission to go to Tibet?

VH: Well, it's a strange process. Tibet is one of the only parts of China where you have to get a special permit. That requires advanced planning. We didn't have much time for advanced planning because the Ambassador didn't even get a green light to go to Tibet until a week before the trip or something. I knew some people who could help me get the right travel agent to help with the permit and tickets. We had to not just get the plane tickets to get over there, but then the train tickets for the ride to Tibet.

I only knew of the one train that the Ambassador was on and asked for tickets for that. But then once we get to Xining, which is in the Qinghai province on the Tibetan plateau where the train will start its journey to Lhasa, we had to meet up with a Chinese woman who had the tickets. It was one of those funny experiences where she came to our hotel, but we recognized she was someone who had been watching us as we were filming in the city that day in Xining. Then, later that night we were also filming and we would find her around watching us too.

I think once you get tickets to Tibet, you're definitely on the government's radar because it's such a sensitive territory for them and a sensitive topic, and especially an American with a camera, it's not something they like.

I think their main strategy on the train with threatening to kick us off, was stopping us from shooting. They were kind of detaining us and treating us like stowaways, breaking us down until I cried and went and grabbed my permit and my passport and begged. They said, okay, if the Ambassador's entourage makes room for you, you can stay, but you're not supposed to film and all these other all these other rules.

It was traumatic because we had also just traveled half way around the world, and we were totally jet lagged, and then had gotten to Xining and had a great day of filming and then suddenly everything came to a halt. We thought we were going to be dumped in the middle of nowhere at 3 AM, two women with a bunch of equipment on a route that's generally just traders and prostitutes. So they had us scared.

NP: The films features footage of Jon when he was at one of the Jasmine Spring protests, which was very problematic for him. Did you shoot that footage?

VH: The propaganda video that was made about the Jasmine Spring, we did not…and the police footage, when they're slamming the camera, that's archive actually. But it did seem like a critical moment of maybe exasperation on the part of the U.S. government that he would even have stumbled into that as a diplomat. I mean, yes, technically as a diplomat maybe he should have stayed out of it, but I think he was saying, in a delicate diplomatic way, actually I do want to know what's going on with the people and it matters.

NP: You were talking about your trip to France and the problems with getting distribution for non-European documentaries. You've got an Indigogo fundraiser to help to try to get the film completed and distributed — what are your hopes and goals with that?

VH: We would love to be able to finish the film… We're basically almost at a picture lock. We have a little more polishing to do and a sound mix to complete and then funds for festivals, possibly for distribution and marketing. It's a process with a documentary where you're raising money over time and stages and proving your work along the way. I feel like this was finally the only time I was comfortable doing a crowdfunding campaign. We were far enough along and could really show something good to the public at Tribeca. That was a good thing, with sold out screenings and some nice press…

NP: Finally, what do you hope this film will instill in the viewer?

VH: It's too big of an ambition, but I would love it if we could just remove the cone of silence that exists around China. Because I think it really is harmful and hurtful to the people there that we're not speaking honestly about what's going on. While its wonderful there's been economic growth, that comes at a price where the government is increasingly repressive and people need a voice. The more we can champion that desire for rule of law, civil society, having a voice, the better it is for people there. And if we are interacting and we are thinking about longer term, it can't just be about the money. It can't. We're going to end up with a world of authoritarian countries. I mean seriously, it's not like we're making democracy look very attractive right now, so we certainly have to get our house in order. But we also have to be paying attention to how much authoritarianism can look good to other countries if China's so quick to rise economically.

NP: Right. I think that's what's so important about that quote that you got from Jon when he talks about how his job's more difficult because our credibility has been shot. Because we can't tell other countries to get their houses in order until we get our own house in order. You see very graphically in this film the price we're paying for our own bad behavior.

VH: Right.

NP: It's really hard for us to tell China, you can't do that, when we're doing the same thing.

VH: Yes, that is true, and then at the same time, it doesn't mean we can't speak up about what's happening in China… Because it comes up frequently; It's an excuse to say, yes, but America's so guilty of war crimes and human rights abuses. And yes, we are. But we can admit that, and we can improve on our own system, and at the same time still acknowledge what's really going on in China, because we're impacting it. To not acknowledge it, is to be hurting the people in China, and I don't think we should be a part of that.

For more information visit alleyesandears.org, watch the trailer below, and follow @VHopeful and @alleyesearsdoc on Twitter. If you’d like to support All Eyes And Ears, visit the Indiegogo page.