Check this out:

GRESTEN, Austria (Reuters) - As Christmas nears, Austrian children

hoping for gifts from Santa Claus will also be watching warily for

"Krampus," his horned and hairy sidekick.

In folklore, Krampus was a devil-like figure who drove away evil

spirits during the Christian holiday season.

Traditionally, he appeared alongside Santa around December 6, the

feast of St. Nicholas, and the two are still part of festivities in

many parts of central Europe.

But these traditions came under the spotlight in Austria this year,

after reports last week that Santa -- also known as St Nicholas,

Father Christmas or Kris Kringle -- had been banned from visiting

kindergartens in Vienna because he scared some children.

Officials denied the reports, but said from now on only adults the

children knew would be able to don Santa's bushy white beard and red

habit to visit the schools.

Now, a prominent Austrian child psychiatrist is arguing for a ban on

Krampus, who still roams towns and villages in early December.

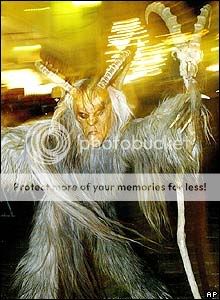

Boisterous young men wearing deer horns, masks with battery-powered

red eyes, huge fangs, bushy coats of sheep's fur, and brandishing

birchwood rods storm down the streets, confronting spectators gathered

to watch the medieval spectacle, which is also staged in parts of

nearby Hungary, Croatia and Germany's Bavaria state.

Anyone who doesn't dodge or run away fast enough might get swatted --

although not hard -- with the rod.

"The Krampus image is connected with aggression, and in a world that

is anyway full of aggression, we shouldn't add figures standing for

violence... and hell," child psychiatrist Max Friedrich said.

Friedrich, who says Krampus is scary because people can't communicate

with a mask, doesn't get much of a hearing in the traditionalist towns

of Lower Austria and the Salzburg and Tyrol regions that hold the most

elaborate Krampus processions.

In Gresten, 3,000 people, including many children, packed the kerbs of

Dorfstrasse one recent night to await his coming.

The horned figure suddenly burst out of a dark corner, shouting

menacingly at onlookers and waving his birchwood whip.

As he knocked over a metal crowd barrier and waded into the

spectators, a boy who identified himself as Simon flinched.

"Don't worry," a nearby adult assured Simon. "Krampus won't do

anything to you. He's not allowed to."

Johann Leichtfried, a young Krampus actor in Gresten, defended his

role and said most children were fascinated by Krampus's symbolism.

"Krampus is for the kids."

But not everyone agrees.

Listeners of Austrian youth radio station FM4 shared the horror they

felt when first confronted the figure.

"Krampus scared ... me when I was seven," said one, identified as Riem

on FM4's Web site. "I panicked that I was never going to see my father

again because a hoofed human wanted to throw me in his wooden

backpack."

But Friedrich conceded there had been few known cases of "Krampus trauma."

He said Krampus remained a popular custom probably because "there's a

phenomenon of finding fear attractive," pointing for example to the

frequently frightening, sometimes gruesome, plot twists in the classic

fairy-tales of the Grimm brothers.

Sometimes, Krampus can get carried away -- in some towns in the Tyrol

and Salzburg areas, some of the horned devils have lost control after

downing a few too many beers or schnapps.

"In Tyrolean communities ... the Krampus actors have to wear a number

so everyone can know who the bad guy is behind the mask, just in

case," said Friedrich.

GRESTEN, Austria (Reuters) - As Christmas nears, Austrian children

hoping for gifts from Santa Claus will also be watching warily for

"Krampus," his horned and hairy sidekick.

In folklore, Krampus was a devil-like figure who drove away evil

spirits during the Christian holiday season.

Traditionally, he appeared alongside Santa around December 6, the

feast of St. Nicholas, and the two are still part of festivities in

many parts of central Europe.

But these traditions came under the spotlight in Austria this year,

after reports last week that Santa -- also known as St Nicholas,

Father Christmas or Kris Kringle -- had been banned from visiting

kindergartens in Vienna because he scared some children.

Officials denied the reports, but said from now on only adults the

children knew would be able to don Santa's bushy white beard and red

habit to visit the schools.

Now, a prominent Austrian child psychiatrist is arguing for a ban on

Krampus, who still roams towns and villages in early December.

Boisterous young men wearing deer horns, masks with battery-powered

red eyes, huge fangs, bushy coats of sheep's fur, and brandishing

birchwood rods storm down the streets, confronting spectators gathered

to watch the medieval spectacle, which is also staged in parts of

nearby Hungary, Croatia and Germany's Bavaria state.

Anyone who doesn't dodge or run away fast enough might get swatted --

although not hard -- with the rod.

"The Krampus image is connected with aggression, and in a world that

is anyway full of aggression, we shouldn't add figures standing for

violence... and hell," child psychiatrist Max Friedrich said.

Friedrich, who says Krampus is scary because people can't communicate

with a mask, doesn't get much of a hearing in the traditionalist towns

of Lower Austria and the Salzburg and Tyrol regions that hold the most

elaborate Krampus processions.

In Gresten, 3,000 people, including many children, packed the kerbs of

Dorfstrasse one recent night to await his coming.

The horned figure suddenly burst out of a dark corner, shouting

menacingly at onlookers and waving his birchwood whip.

As he knocked over a metal crowd barrier and waded into the

spectators, a boy who identified himself as Simon flinched.

"Don't worry," a nearby adult assured Simon. "Krampus won't do

anything to you. He's not allowed to."

Johann Leichtfried, a young Krampus actor in Gresten, defended his

role and said most children were fascinated by Krampus's symbolism.

"Krampus is for the kids."

But not everyone agrees.

Listeners of Austrian youth radio station FM4 shared the horror they

felt when first confronted the figure.

"Krampus scared ... me when I was seven," said one, identified as Riem

on FM4's Web site. "I panicked that I was never going to see my father

again because a hoofed human wanted to throw me in his wooden

backpack."

But Friedrich conceded there had been few known cases of "Krampus trauma."

He said Krampus remained a popular custom probably because "there's a

phenomenon of finding fear attractive," pointing for example to the

frequently frightening, sometimes gruesome, plot twists in the classic

fairy-tales of the Grimm brothers.

Sometimes, Krampus can get carried away -- in some towns in the Tyrol

and Salzburg areas, some of the horned devils have lost control after

downing a few too many beers or schnapps.

"In Tyrolean communities ... the Krampus actors have to wear a number

so everyone can know who the bad guy is behind the mask, just in

case," said Friedrich.